Meetings > Previous Meetings > October 2012

|

RISC OS User Group Of London

Meetings > Previous Meetings > October 2012 |

|

All dialog is Paul Fellows, except audience questions that are marked Q:. Minor hesitation and in-conversation self corrections edited.

Thanks very much for inviting me guys, god knows what you're all doing here, after 25 years of doing this. I'm very pleased to talk to you about what me and my boys did all that time ago. Before we talk about that I've got to explain 'why?', and that means who I am and how we got to where we got to.

Obviously we started off with the best machine in the world, ever, the BBC Micro model B. That's what got me into all of this. Though my first machine was a Sinclair ZX80 which I acquired for free, that I upgraded with a ZX81 ROM which meant the keyboard was all wrong. My first sensible computer was the BBC model B that I bought when I was a student at Cambridge, I was encouraged to do that as a friend was building an Acorn Atom in his room, a chap called Steve Barlow, which I thought was a fantastic thing, and I abandoned studying chemistry, which is what I was supposed to be doing, and started playing with computers all day.

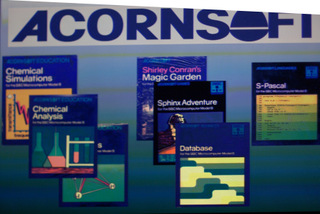

By the time

I'd finished my degree, I'd written this lot for Acornsoft. A bit of a chemical theme going

on here, using my chemistry degree that I should have been studying, but was writing programs about it

instead. Shirley Conran's Magic Garden was the worst program in the world ever. I was forced to write

that one as Chris Curry did some bizarre publishing deal with Shirley Conran's publishers. I apologise

profusely for that program if anyone ever saw it. That's the only one in its shrink wrap, it's so

completely useless I never opened it. Sphinx Adventure warped the minds of a whole generation. Acornsoft

Database was very good for what it did, but completely made obsolete by Mark Colton's View series.

By the time

I'd finished my degree, I'd written this lot for Acornsoft. A bit of a chemical theme going

on here, using my chemistry degree that I should have been studying, but was writing programs about it

instead. Shirley Conran's Magic Garden was the worst program in the world ever. I was forced to write

that one as Chris Curry did some bizarre publishing deal with Shirley Conran's publishers. I apologise

profusely for that program if anyone ever saw it. That's the only one in its shrink wrap, it's so

completely useless I never opened it. Sphinx Adventure warped the minds of a whole generation. Acornsoft

Database was very good for what it did, but completely made obsolete by Mark Colton's View series.

S-Pascal was a Pascal compiler that I wrote, in BASIC, and was my thesis for my post-graduate work at the computer lab, so I did that and got paid for it as Acornsoft published it. The whole of a Pascal compiler written in BASIC in the 32KB of a BBC Micro. So you had your program, the compiler and the object code it created, you'll notice this one is published on a floppy disc, but they also published it on cassette if you were a real masochist. You could load the compiler off cassette, and compile a program that was about 1.5KB long, fabulous.

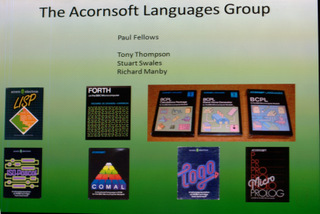

As a result

of writing that Pascal compiler, I got offered the job of taking over running Acornsoft's

languages group. Myself, Tony Thompson, Stuart Swales and Richard Manby were responsible for

getting all of this lot out the door. We didn't write any of them,

but we managed and tested all of these. LISP was

written by Arthur Norman at the computer lab, Forth by Richard de Grandis-Harrison who went on to be

a driving force in other things, like Symbian I think. Martin Richards, who invented BCPL, and his

brother were responsible for the compilers over there and the LOGO implementation. There were some

dudes from London that did the Prolog, David Christiansen did COMAL and Ben and Lionel at Acorn did

the ISO Pascal compiler, which was fully validated and fitted on a 16KB ROM.

As a result

of writing that Pascal compiler, I got offered the job of taking over running Acornsoft's

languages group. Myself, Tony Thompson, Stuart Swales and Richard Manby were responsible for

getting all of this lot out the door. We didn't write any of them,

but we managed and tested all of these. LISP was

written by Arthur Norman at the computer lab, Forth by Richard de Grandis-Harrison who went on to be

a driving force in other things, like Symbian I think. Martin Richards, who invented BCPL, and his

brother were responsible for the compilers over there and the LOGO implementation. There were some

dudes from London that did the Prolog, David Christiansen did COMAL and Ben and Lionel at Acorn did

the ISO Pascal compiler, which was fully validated and fitted on a 16KB ROM.

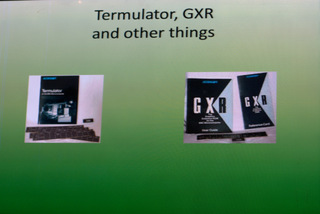

The languages

group kind of went off-piste, management didn't really care what we did as long as it made money,

we got involved in several other things; Termulator a terminal emulator for a VT52 terminal, which

nobody used, we were very glad as I couldn't really see why.

The languages

group kind of went off-piste, management didn't really care what we did as long as it made money,

we got involved in several other things; Termulator a terminal emulator for a VT52 terminal, which

nobody used, we were very glad as I couldn't really see why.

Most importantly to our story tonight we wrote the graphics extension ROM for the BBC Micro. It had been mentioned, and there was a little bit in one of the User Guides, that was reserved for the graphics extension ROM and that tweaked my interest. I thought that someone really ought to do that. And so Richard Manby in the languages group (working for me) when he ran out of languages to implement he produced a graphics extension that did ellipses, flood fills and that stuff and produced the graphics extension ROM and all of that then got incorporated into the BBC Master 128 Operating System and this is crucial to the story as it's the first time Acornsoft, which was a separate company, got to do some system software that went into the machine, so you can see where this is going, can't you.

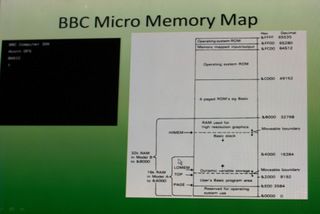

Right,

here is a little lesson on the history of the memory map of the BBC Micro. So on the slide here

you have got the BBC Computer, 32K, DFS, BASIC, the classic screen that it came up with, and on this

side over here you've got the memory map of how that 64KB of address space was organised. On the bottom

here we've got the RAM from 0 of 0x8000 and then 16KB of ROM space and then the Operating system

ROM and the memory mapped IO at the top. Very simple, and out of scale, can you see where it says

'movable boundary',

graphics memory started here and worked its way downwards, but more likely it came down to about

here if you put it into high resolution graphics, so 20K of your 32K went to graphics, and the

Operating System had the first 4K-8K, so there wasn't very much left for you if you used high

resolution graphics modes.

Right,

here is a little lesson on the history of the memory map of the BBC Micro. So on the slide here

you have got the BBC Computer, 32K, DFS, BASIC, the classic screen that it came up with, and on this

side over here you've got the memory map of how that 64KB of address space was organised. On the bottom

here we've got the RAM from 0 of 0x8000 and then 16KB of ROM space and then the Operating system

ROM and the memory mapped IO at the top. Very simple, and out of scale, can you see where it says

'movable boundary',

graphics memory started here and worked its way downwards, but more likely it came down to about

here if you put it into high resolution graphics, so 20K of your 32K went to graphics, and the

Operating System had the first 4K-8K, so there wasn't very much left for you if you used high

resolution graphics modes.

This too

is crucial because, the model B was a very popular machine but

a lot of scrambling around and the competition coming out with machines like the Commodore 64 and

the Amiga coming along with even more memory, 256KB or even 512KB of RAM, Acorn had to do something

and one of my friends, Martin Gilbert, was beavering away in the background, building the Model C

which became the Master, but it was taking forever so we had to do something,

and Watford Electronics invented * a way of adding more memory which

was to create a shadow bank of memory for the big chunk of the video memory, and if the

processor tried to access the memory in that range with an instruction that had been fetched

from a range in the operating system ROM then it must be trying to access the screen so it

would magically flip it over to the other bank of memory and let you access the screen and let

the operating system do that and flip it back. Whereas if the address range of the instruction

fetch was anywhere else then is just accessed the normal memory, so your program got to access

normal RAM and the operating system graphics routines got to see this other memory. Which meant

that you couldn't poke the screen because your program couldn't get at it, it had

to go through the proper operating system calls, and that broke all sorts of illegally written

software that cheated its way around the APIs and we were very happy about that because all

our stuff worked.

This too

is crucial because, the model B was a very popular machine but

a lot of scrambling around and the competition coming out with machines like the Commodore 64 and

the Amiga coming along with even more memory, 256KB or even 512KB of RAM, Acorn had to do something

and one of my friends, Martin Gilbert, was beavering away in the background, building the Model C

which became the Master, but it was taking forever so we had to do something,

and Watford Electronics invented * a way of adding more memory which

was to create a shadow bank of memory for the big chunk of the video memory, and if the

processor tried to access the memory in that range with an instruction that had been fetched

from a range in the operating system ROM then it must be trying to access the screen so it

would magically flip it over to the other bank of memory and let you access the screen and let

the operating system do that and flip it back. Whereas if the address range of the instruction

fetch was anywhere else then is just accessed the normal memory, so your program got to access

normal RAM and the operating system graphics routines got to see this other memory. Which meant

that you couldn't poke the screen because your program couldn't get at it, it had

to go through the proper operating system calls, and that broke all sorts of illegally written

software that cheated its way around the APIs and we were very happy about that because all

our stuff worked.

But it still

wasn't enough, and Acorn thought 'how the hell can we add any more' and they made the B+ 128,

because the Master was even later. The way they did this was stuff another 64KB into some of those

ROM slots, if I nip back to the memory map, paged ROMs between 0x8000 and 0xBFFF you have

the paged ROM area, so BASIC, ADFS and other ROMs would live within this space and there

was a page register that would say which one was paged in

but you could put RAM there as well. The B+ 128 had four 16K RAMs stuffed into that area, and I've

drawn a little map of it here, so at the top we've got the operating system and the ROMs,

BASIC would live in here normally, but we've got 4 pages of RAM over here making another 64K that

was really hard to get at. This is the shadow memory that I talked about from the B+ that only the

operating system graphics routines could get at. But I had this idea that people wanted to write

larger BASIC programs and if we were going to sell a machine with 128KB of RAM we really ought

to let you write a bigger program than the previous version.

But it still

wasn't enough, and Acorn thought 'how the hell can we add any more' and they made the B+ 128,

because the Master was even later. The way they did this was stuff another 64KB into some of those

ROM slots, if I nip back to the memory map, paged ROMs between 0x8000 and 0xBFFF you have

the paged ROM area, so BASIC, ADFS and other ROMs would live within this space and there

was a page register that would say which one was paged in

but you could put RAM there as well. The B+ 128 had four 16K RAMs stuffed into that area, and I've

drawn a little map of it here, so at the top we've got the operating system and the ROMs,

BASIC would live in here normally, but we've got 4 pages of RAM over here making another 64K that

was really hard to get at. This is the shadow memory that I talked about from the B+ that only the

operating system graphics routines could get at. But I had this idea that people wanted to write

larger BASIC programs and if we were going to sell a machine with 128KB of RAM we really ought

to let you write a bigger program than the previous version.

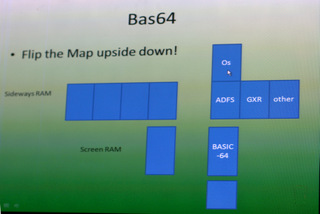

So I had

this mad idea which was to put a BASIC interpreter down here and let it

access your program spread across these four ROM slots, but of course they all lived in the

same address space. By finding all the places in the assembly language of the BASIC interpreter where

it accessed the source code of your program or its variables, you discovered they were all

done with one particular mode of addressing, the 'indirect comma y' form of addressing, so we

could do that and stick an extra byte of address in there and poke a hardware register in

order to let you access these chunks as if it was a 64K address space. So we got that version

of BASIC all to work and there was a lot of page swapping of the ROMs going on. I went

along and proposed that we do this too Roger Wilson, now Sophie Wilson, who was responsible

for BASIC

and got the comment "You're insane, that's suicide, it'll be impossible to do", so we

did it anyway and it got shipped with the B+ 128 and the Master that came along afterwards.

Tony Thompson from my group did this and Acorn were very grateful at the time as they were

able to say "It's bigger, and you've got more memory", that really put my guys on the map as being

able to do things that Sophie thought were impossible. This is good and you can see where this

story is going.

So I had

this mad idea which was to put a BASIC interpreter down here and let it

access your program spread across these four ROM slots, but of course they all lived in the

same address space. By finding all the places in the assembly language of the BASIC interpreter where

it accessed the source code of your program or its variables, you discovered they were all

done with one particular mode of addressing, the 'indirect comma y' form of addressing, so we

could do that and stick an extra byte of address in there and poke a hardware register in

order to let you access these chunks as if it was a 64K address space. So we got that version

of BASIC all to work and there was a lot of page swapping of the ROMs going on. I went

along and proposed that we do this too Roger Wilson, now Sophie Wilson, who was responsible

for BASIC

and got the comment "You're insane, that's suicide, it'll be impossible to do", so we

did it anyway and it got shipped with the B+ 128 and the Master that came along afterwards.

Tony Thompson from my group did this and Acorn were very grateful at the time as they were

able to say "It's bigger, and you've got more memory", that really put my guys on the map as being

able to do things that Sophie thought were impossible. This is good and you can see where this

story is going.

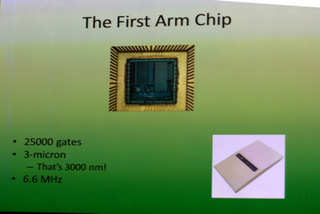

Meanwhile,

Sophie and Steve had been incredibly busy designing the ARM chip, and there is a picture

of the first ARM chip with its lid off. The statistics about it are amazing, 25 thousand

transistors, based on 3 micron technology

which is 3000 nanometres in today's money, huge by comparison to anything going on today. It was

running at 6.6MHz and taking one cycle per instruction to do its work. It only had 26 different

instructions at the time and there's no multiply on this device, which came later with the 2micron

version, the die-shrink. They built it first and put it in the very nice second-processor cases,

pictured here. You could turbo-charge your BBC but getting one of these systems and putting it on

the side, if you could get hold of one. They were really hard to get hold of and eventually sold as

an ARM development system, they were a bit snotty about who was allowed to buy them, they didn't put them

on general sale. In fact we had some trouble getting them at Acornsoft and I had to send Stuart Swales

down to the lab,

signed for all the parts, and brought them back and we built four ourselves. This was the only way to get

hold of these wonderful things. I thought it was absolutely amazing to boot one of these up with BBC BASIC V,

and see that I had a whole Megabyte of RAM to play with and the thing was unbelievably fast compared to the

poor old BBC which we had before.

Meanwhile,

Sophie and Steve had been incredibly busy designing the ARM chip, and there is a picture

of the first ARM chip with its lid off. The statistics about it are amazing, 25 thousand

transistors, based on 3 micron technology

which is 3000 nanometres in today's money, huge by comparison to anything going on today. It was

running at 6.6MHz and taking one cycle per instruction to do its work. It only had 26 different

instructions at the time and there's no multiply on this device, which came later with the 2micron

version, the die-shrink. They built it first and put it in the very nice second-processor cases,

pictured here. You could turbo-charge your BBC but getting one of these systems and putting it on

the side, if you could get hold of one. They were really hard to get hold of and eventually sold as

an ARM development system, they were a bit snotty about who was allowed to buy them, they didn't put them

on general sale. In fact we had some trouble getting them at Acornsoft and I had to send Stuart Swales

down to the lab,

signed for all the parts, and brought them back and we built four ourselves. This was the only way to get

hold of these wonderful things. I thought it was absolutely amazing to boot one of these up with BBC BASIC V,

and see that I had a whole Megabyte of RAM to play with and the thing was unbelievably fast compared to the

poor old BBC which we had before.

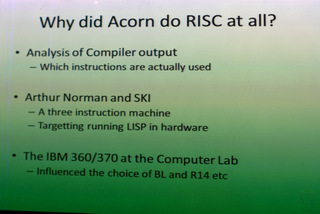

I just

wanted to say a bit about why Acorn decided to do this whole RISC thing at all, Acorn was

a manufacturer of home computers, why on earth would you be crazy enough to design your own chip?

I just

wanted to say a bit about why Acorn decided to do this whole RISC thing at all, Acorn was

a manufacturer of home computers, why on earth would you be crazy enough to design your own chip?

Sophie did an analysis of the compiler output for a lot of common compilers as part of the process of trying to choose which chip we should use next, we were looking at things like the 68000 and the National Semiconductor 16032, or 32016 as it got renamed. I don't know if you remember, a second processor was done with that 32016 and Nat Semi had produced a poster that said "32016 is not a late 16 bit machine it's an early 32 bit machine", a year later we crossed out 'early' and wrote 'late' on it. This analysis showed that all of the complicated instructions and all of complicated mem-copies, the compilers just don't generate them. They generate Load/Store, add, subtract, and/or, compare, branch, that's about it really, the rest of them, unless you're writing in assembler, you just don't use them, so they're a complete waste.

Now, the aforementioned, Arthur Norman, who had written the LISP interpreter for the BBC Micro, and was in and out of Acorn the whole time, had come up with a design for a machine with 3 instructions called the SKI machine. Whose instructions were called 'S', 'K' and 'I' and it ran LISP in hardware and he built one of these things, it never worked, it was so big and covered in wire-wrap it was always broken. The idea was to prove that you really didn't need very many instructions for a general purpose machine.

Q: What were the three instructions, what did they do?

I can point you at his paper if you like, I've read it but I still don't understand it. Are you familiar with the LISP programming language? Basically you could take the right value, the left value or skip onto the next instruction, those were really only the three primitives you need in LISP. That's what this machine did, only I've read his paper and I still don't really get it. Also at the time the computer lab had just got their IBM 370, and we noticed that had Branch and Link and put the program counter into R14 rather than having Jump-To-Subroutine, automatic stamp. That had the model of a user-accessable register for return-addresses, and returning by just using MOV R14 PC and why have a special purpose RTS instruction. All of those things together meant that they thought "Right, it is sufficiently simple that we could design this". and so they did it, mostly because they could and because of all the work going on in the computer lab at the time.

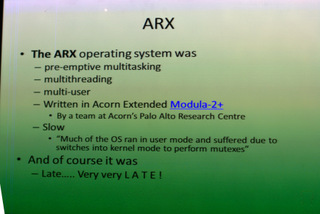

Acorn had also

opened a research centre in Paolo Alto and set about the process of writing an operating system

to run on this chip, ARX. This ARX operating system was preemptively multi tasking, multi-threaded,

multi-user, written in Acorn-extended Modula2+, god-alone knows why they chose that language.

I did some tests on the compiler for it, which was the only compiler there was for the ARM at

this point. I gave it the task of taking an

X and Y coordinate and working out where that would be as an address in memory, so we had to add the

base address to the Y coordinate times the row width and add X, not exactly complicated it is two

adds and a multiply. The Modula2 compiler generated 25 instructions and then did Branch and Link

general multiply, so it was a bit slow. It was slow because it was written in a high-level language

and because, this a quote from Wikipedia, "much of the operating system ran in user-mode and suffered

from kernel switches to perform the mutexes" in order to do all of the multi processing that's

mentioned above. Of course the real problem with it was that it was very, very late. So the

hardware was starting to be made

and the software was obviously nowhere to be seen and predicted to be another six to nine months

away from being ready to ship. Hence this is why project Arthur got the job, born in this

absolute crisis of the hardware coming into existence.

Acorn had also

opened a research centre in Paolo Alto and set about the process of writing an operating system

to run on this chip, ARX. This ARX operating system was preemptively multi tasking, multi-threaded,

multi-user, written in Acorn-extended Modula2+, god-alone knows why they chose that language.

I did some tests on the compiler for it, which was the only compiler there was for the ARM at

this point. I gave it the task of taking an

X and Y coordinate and working out where that would be as an address in memory, so we had to add the

base address to the Y coordinate times the row width and add X, not exactly complicated it is two

adds and a multiply. The Modula2 compiler generated 25 instructions and then did Branch and Link

general multiply, so it was a bit slow. It was slow because it was written in a high-level language

and because, this a quote from Wikipedia, "much of the operating system ran in user-mode and suffered

from kernel switches to perform the mutexes" in order to do all of the multi processing that's

mentioned above. Of course the real problem with it was that it was very, very late. So the

hardware was starting to be made

and the software was obviously nowhere to be seen and predicted to be another six to nine months

away from being ready to ship. Hence this is why project Arthur got the job, born in this

absolute crisis of the hardware coming into existence.

Q: Is there a relationship between Arthur Norman and Arthur?

I'm not sure, that's a good question, I did think about that. I believe that the word Arthur comes from the fact they wanted ARm on THURsday, because of the crisis, but that's my memory of it, and there's a bit of debate and other people may say different things.

Officially it was Project Arthur, but Arthur Norman was never involved, even though he was around and involved in the design of the ARM.

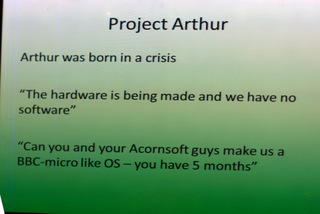

I was hauled in,

in front of the board of directors at Acorn, and they said "the hardware is being

made and we have got no software, you guys aren't doing very much at Acornsoft, can you make us a

BBC like operating system, you've got 5 months?", as that's when the hardware is going to hit the

streets. And like an idiot I said "yes", we hadn't got very much to do. The reason they came to us

was because we'd done the graphics extension ROM for the Master, we'd been part of the recent

machine that had gone out the door and because we'd done the fancy BASIC interpreter that could

access more memory, thus proving we could do hard things,

and done all the languages you could possibly want for the BBC Micro, so we really didn't have

much else to do.

I was hauled in,

in front of the board of directors at Acorn, and they said "the hardware is being

made and we have got no software, you guys aren't doing very much at Acornsoft, can you make us a

BBC like operating system, you've got 5 months?", as that's when the hardware is going to hit the

streets. And like an idiot I said "yes", we hadn't got very much to do. The reason they came to us

was because we'd done the graphics extension ROM for the Master, we'd been part of the recent

machine that had gone out the door and because we'd done the fancy BASIC interpreter that could

access more memory, thus proving we could do hard things,

and done all the languages you could possibly want for the BBC Micro, so we really didn't have

much else to do.

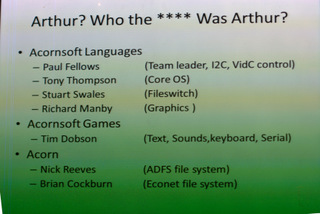

Who were we?

It was the Acornsoft languages group, myself, I was the team leader, I was the

fool that said "yes we can do it". I got to write the I2C drivers, actually I was given some

I2C drivers by John Biggs, who's at ARM today, they were written in Modula2 which had been ripped

off out of the ARX implementation, he said "here, this is how you do it, make the Real Time Clock work,

that'll be fine, just test it for me will you?". Not having a compiler that worked on the nascent

version of Arthur that we had at the time, I transliterated it all into assembler, it went 400 times

faster and it got slightly upset that I was driving the bus too fast. I also did things like the colour

palette.

Who were we?

It was the Acornsoft languages group, myself, I was the team leader, I was the

fool that said "yes we can do it". I got to write the I2C drivers, actually I was given some

I2C drivers by John Biggs, who's at ARM today, they were written in Modula2 which had been ripped

off out of the ARX implementation, he said "here, this is how you do it, make the Real Time Clock work,

that'll be fine, just test it for me will you?". Not having a compiler that worked on the nascent

version of Arthur that we had at the time, I transliterated it all into assembler, it went 400 times

faster and it got slightly upset that I was driving the bus too fast. I also did things like the colour

palette.

Tony Thompson, who had done that implementation of BASIC 64, he got to do the core of the operating system, so the real guts of Arthur itself. That brought it out of reset, powered it up, organised all the memory and so forth. We had a really interesting time with part of that, we had one of the machines that we just could not get this thing to boot reliably. You could boot it, turn it off, reboot it and sometimes it would work and sometimes it wouldn't. It turned out, it would boot fine if you left it long enough, but if you didn't turn it off for very long then it didn't reset properly, and this was because the fan on the board was still spinning and the back EMF on the fan was enough power to keep the ARM running. And that's why you've got an ARM in your phone today, it would take no power to keep a 3 micron ARM with 25000 transistors would run for 30 seconds off the energy stored in the fan.

Stuart Swales, wrote fileswitch and I think the Heap manager as well, we couldn't have done it without Stuart, he just fixed everything.

Richard Manby, graphics extension ROM author, did the graphics and in RISC OS 2 he went on to do Draw which is really quite a fantastic program.

Then we've got our ace games programmer out of semi-retirement where he'd been out writing games for the beeb with no market for them, Tim. Tim works at Broadcom these days, he did the text, the sound, the keyboard, the serial. We drafted in a couple of other guys from Acorn as the team grew.

We got Nick Reeves who did the disk filing system stuff and Brian Cockburn, that was the team, just those guys. Tony is at ARM, Stuart has retired, Richard Manby works at ANT in Cambridge on embedded browsers, Tim works on chips with Sophie at Broadcom, things like Raspberry Pi core chips and related work, Nick Reeves is at ARM and Brian is at Amino. Amino is a company that I started with Martin Gilbert in 1997, Martin designed the Master 128. If you look inside one of these Amino set top boxes you find there's a boot ROM in the NOR flash, and a filing system on the NAND flash, and the boot ROM doesn't half look like the core operating system and a load of separate relocatable modules, it boots up and runs *exec !Boot and that's inside the NAND flash which goes 'run Linux'. I think we sold 4.5 million of those set-top-boxes, which is more instances of an operating system than Acorn ever managed.

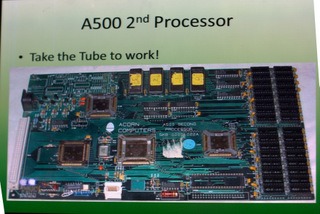

Things got

serious when I got some hardware on my desk, this is the first piece of hardware

I got (A500 second processor card), you can see the four core chips, the ARM, MEMC, VIDC and

IOC, in their square flat-pack holders, the RAM over there,

some operating system software of some sort in these EEPROMs here, and the TUBE interface.

So this was plugged into, via a tube interface, a BBC Micro, so it was a giant second

processor (as it says on the board "A500 second processor"). This was the development

board that we had, we first had one and gradually got to the point of having one each to

do the development work on. You could attach a keyboard to it, graphics output from it to

a monitor, so gradually the functionality of Arthur came to life and you could migrate

more and more of the IO features over onto the board from the BBC Micro. Of course

this thing could never run entirely standalone it always needed that host micro

to get it going. We got everything going, the sound, graphics, the memory management and

everything running on here as the initial systems. There's still quite a few of these boards

around and they still work.

Things got

serious when I got some hardware on my desk, this is the first piece of hardware

I got (A500 second processor card), you can see the four core chips, the ARM, MEMC, VIDC and

IOC, in their square flat-pack holders, the RAM over there,

some operating system software of some sort in these EEPROMs here, and the TUBE interface.

So this was plugged into, via a tube interface, a BBC Micro, so it was a giant second

processor (as it says on the board "A500 second processor"). This was the development

board that we had, we first had one and gradually got to the point of having one each to

do the development work on. You could attach a keyboard to it, graphics output from it to

a monitor, so gradually the functionality of Arthur came to life and you could migrate

more and more of the IO features over onto the board from the BBC Micro. Of course

this thing could never run entirely standalone it always needed that host micro

to get it going. We got everything going, the sound, graphics, the memory management and

everything running on here as the initial systems. There's still quite a few of these boards

around and they still work.

The first

stand alone machine, the A500, which is very confusing because they're both called A500,

but the other one was the A500 second processor. There's a photo of said machine with its

lid on and lid off. I thought it was quite smart, this design with this plastic moulding

on the front and the keyboard that plugged in. I think this is actually my computer,

I can tell it's mine because it's got red stickies on some of the function keys,

to change the names of what those buttons did, because the keyboard was designed for ARX

and had some weird buttons on it that nobody ever knew what they were supposed to do, so we

stuck some labels on, I think it was Tipex on this one to make it more appropriate. It's booted

up there running what seems to be RISC OS 2 to me. Inside you've got the floppy drive, hard drive,

podule bus, you've all seen this, it's very similar to any other Archimedes. There's the fan that

you have to stop in order to reboot it.

The first

stand alone machine, the A500, which is very confusing because they're both called A500,

but the other one was the A500 second processor. There's a photo of said machine with its

lid on and lid off. I thought it was quite smart, this design with this plastic moulding

on the front and the keyboard that plugged in. I think this is actually my computer,

I can tell it's mine because it's got red stickies on some of the function keys,

to change the names of what those buttons did, because the keyboard was designed for ARX

and had some weird buttons on it that nobody ever knew what they were supposed to do, so we

stuck some labels on, I think it was Tipex on this one to make it more appropriate. It's booted

up there running what seems to be RISC OS 2 to me. Inside you've got the floppy drive, hard drive,

podule bus, you've all seen this, it's very similar to any other Archimedes. There's the fan that

you have to stop in order to reboot it.

Then the real machines came along, the Archimedes, they changed one important thing, the keyboard. A different style of keyboard and keyboard connector. I don't quite know where the keyboard came from, but there was obviously a micro in there which would chuck it (the keyboard data) to us down the serial lead. One of my funny stories is trying to debug the interface between Tony's software and the keyboard, myself and Stuart and Tony and Bruce (Brian Cockburn) were there all night trying to get this damn thing to work, because the guys who made the keyboard had got this fantastically useless protocol that they'd come up with. The keyboard sent you 0xFF, you replied 0xFF, then it sent you 0xFF again, you replied 0xFF, then it sent 0xFE, and you were supposed to reply 0xFE. The only trouble was, when you received an 0xFF from it, you didn't know if it was the first one or the second one. We spent ages trying to create some code on the ARM end make it reliably boot up and start the keyboard properly. Eventually, at about 1:30 in the morning I suggested we just send it something illegal, so we sent it F0, well you would wouldn't you?

The keyboard took that and went "oh I don't know how to deal with that, I'll start again" and sent 0xFF, but this time we knew it was the first one, and it's still like that today, because we never could get to the bottom of why it didn't work.

So that's

it with its lid off, all the rest of the bits that were hidden under the drives and so forth.

There's an awful lot of components on there by today's standards, I think it broke the CAD

program because there were more than 512, the CAD program that the guys were trying to use to

design the hardware couldn't handle it.

So that's

it with its lid off, all the rest of the bits that were hidden under the drives and so forth.

There's an awful lot of components on there by today's standards, I think it broke the CAD

program because there were more than 512, the CAD program that the guys were trying to use to

design the hardware couldn't handle it.

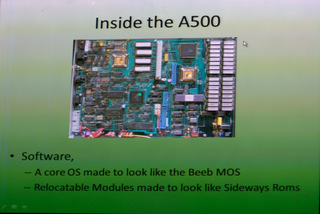

Software wise,

the core operating system was made to look like the BBC MOS, with relocatable

modules made to look like those sideways ROMs,

all the service calls in the Beeb are mirrored by those that go chaining through, but you

don't have to do hardware paging to go from one to the other. Underneath all versions of

RISC OS still have a BBC inside them and in fact if you turn on one of my Amino set top boxes,

with the debug lead in, it doesn't half look like that. In 2007 I finished my association with

Amino set top boxes and did another company with Adrian Chritchlow and some other guys who

were from the Acorn world, and we built something called AlertMe.com in Cambridge which does

home gateways, which are connected to the internet, have a modem in them and through a

collection of Zigbee based sensors have got a burglar alarm function. There's a programmable

infra-red sensor and some magnetics ones

and key-fob and so forth and you can do it really well. Those little sensors have all got

a small processor with 5K RAM and 128K ROM and they don't half look like these inside as well.

All the Amino set top boxes and all the AlertMe sensors are the great grandchildren of all of

this. I kept the faith, I've built another 5 million units that have got an operating system

just like this one in them that probably no one has ever really heard of. Why change a good

plan eh?

Software wise,

the core operating system was made to look like the BBC MOS, with relocatable

modules made to look like those sideways ROMs,

all the service calls in the Beeb are mirrored by those that go chaining through, but you

don't have to do hardware paging to go from one to the other. Underneath all versions of

RISC OS still have a BBC inside them and in fact if you turn on one of my Amino set top boxes,

with the debug lead in, it doesn't half look like that. In 2007 I finished my association with

Amino set top boxes and did another company with Adrian Chritchlow and some other guys who

were from the Acorn world, and we built something called AlertMe.com in Cambridge which does

home gateways, which are connected to the internet, have a modem in them and through a

collection of Zigbee based sensors have got a burglar alarm function. There's a programmable

infra-red sensor and some magnetics ones

and key-fob and so forth and you can do it really well. Those little sensors have all got

a small processor with 5K RAM and 128K ROM and they don't half look like these inside as well.

All the Amino set top boxes and all the AlertMe sensors are the great grandchildren of all of

this. I kept the faith, I've built another 5 million units that have got an operating system

just like this one in them that probably no one has ever really heard of. Why change a good

plan eh?

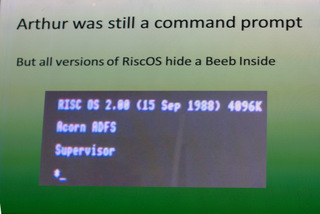

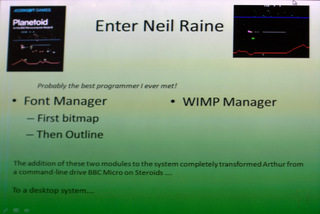

I want to

talk a little about my friend Neil, sadly no longer with us. By that stage we were

here, Arthur 1.something that fired up and looked like that. And it did what the management

had asked us to do, it built a BBC Micro. But Neil came along and said "I've finished writing

these games", that was his best game ever 'Planetoid', defender, a great game. He got interested

in writing a font manager to run on Arthur, so he wrote two, a bitmap one which was all well

and good but a bit clunky and horrible. Then he wrote an outline font manager later that was

so much nicer, which is the one that's still in there today I think.

I want to

talk a little about my friend Neil, sadly no longer with us. By that stage we were

here, Arthur 1.something that fired up and looked like that. And it did what the management

had asked us to do, it built a BBC Micro. But Neil came along and said "I've finished writing

these games", that was his best game ever 'Planetoid', defender, a great game. He got interested

in writing a font manager to run on Arthur, so he wrote two, a bitmap one which was all well

and good but a bit clunky and horrible. Then he wrote an outline font manager later that was

so much nicer, which is the one that's still in there today I think.

And he wrote a Window Manager, I think he just wrote that because he wanted too, the addition of these two modules transformed Arthur from that command-line world to a desktop based system.

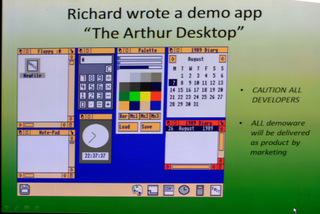

There's a

cautionary tale behind this, Richard Manby wrote this (Arthur Desktop), in BASIC as a demonstration of the

Window Manager and what it could do, using the bitmap fonts and so forth, the outline font manager wasn't

ready at this point. As a piece of demo-ware it escaped into the wild, they burnt it into the

ROM and it's what it boots up with, but it was a demonstration of how you can write programs to

use the window manager, but never underestimate the marketing department, they'll get you every

time, if you write a demo, they'll sell it. How many times have we all been bitten by that one?

There's a

cautionary tale behind this, Richard Manby wrote this (Arthur Desktop), in BASIC as a demonstration of the

Window Manager and what it could do, using the bitmap fonts and so forth, the outline font manager wasn't

ready at this point. As a piece of demo-ware it escaped into the wild, they burnt it into the

ROM and it's what it boots up with, but it was a demonstration of how you can write programs to

use the window manager, but never underestimate the marketing department, they'll get you every

time, if you write a demo, they'll sell it. How many times have we all been bitten by that one?

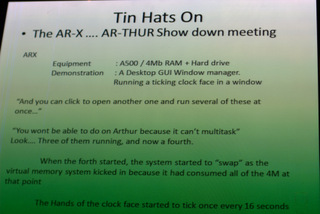

So after

we'd written that, the great show-down meeting happened, as it says here, the

ARX and the ARm on THURsday showdown meeting. In the boardroom at Acorn, in the morning

the team from Paolo-Alto turned up with their 4MB A500 with a hard-drive running ARX to

do a demonstration of how far they'd got and what a wonderful thing it was. But big mistake,

they'd told us what their demo was going to be before hand. So they'd got a ticking clock

running, and they said "and you can click on another one and run several of these at

once, you won't be able to do that on Arthur as it can't multitask, look!", they clicked on

three or four of them and got them running.

When the fourth one started the system started to engage virtual memory and started swapping, on a 4MB

machine and the hands on the clock started ticking once every 16 seconds.

So after

we'd written that, the great show-down meeting happened, as it says here, the

ARX and the ARm on THURsday showdown meeting. In the boardroom at Acorn, in the morning

the team from Paolo-Alto turned up with their 4MB A500 with a hard-drive running ARX to

do a demonstration of how far they'd got and what a wonderful thing it was. But big mistake,

they'd told us what their demo was going to be before hand. So they'd got a ticking clock

running, and they said "and you can click on another one and run several of these at

once, you won't be able to do that on Arthur as it can't multitask, look!", they clicked on

three or four of them and got them running.

When the fourth one started the system started to engage virtual memory and started swapping, on a 4MB

machine and the hands on the clock started ticking once every 16 seconds.

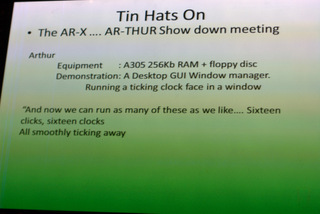

So they

did their demonstration and we turned up, Tim Dobson had written a clock program,

we turned up with an A305 with 256KB RAM, an Arthur desktop and a ticking clock program, and we ran 16 of

them which ticked smoothly, and ARX got cancelled the next day.

So they

did their demonstration and we turned up, Tim Dobson had written a clock program,

we turned up with an A305 with 256KB RAM, an Arthur desktop and a ticking clock program, and we ran 16 of

them which ticked smoothly, and ARX got cancelled the next day.

It (ARX) was hopeless, there was no way that we (Acorn) could afford to go to market with a machine that needed 4MB of RAM and a hard drive, in those days, and even then was going to be that slow. We were absolutely going to have to launch it with the smallest amount of RAM and no hard drive.

Q: When was this?

1986/87, something like that. I think it was Sept 1985 when I had that come to Jesus meeting where they said "Write it in 5 months, we'll have the hardware in early 86", of course the hardware took longer than that, it always does, doesn't it. But so did we, we took a year to get to Arthur 1.20, we shipped a few versions earlier than that.

Q: How much was 4MB of RAM in 1986?

A shit load.

The A500 would have been 3000 ukp worth of computer, and the little A305 and A310 were about 1000 ukp all in. 700 ukp for the smallest system, so still fairly expensive compared to the beebs at 400-500 ukp. The problem was that the price of these systems was ratcheting up, although the functionality was going up. What happened to Acorn, in my opinion, it went to fast up the functionality curve, that the price crept up. It left an enormous gap underneath into which Nintendo, Playstation and everyone else marched with their games engines and took away their core market, that's my view.

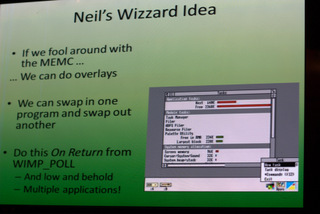

Going

back to Neil, he had a wizard idea, he said at the coffee machine one day "you know what,

if we fool around with MEMC we can do overlays, we can take an application program, use the

memory controller to whisk it away and map it somewhere else in the memory map and put another

program in at 0x8000 (which was where we mapped our applications too), the logical equivalent of PAGE on

the BBC Micro, we can do overlays, switch from one program to another. I thought "that's all very

well Neil but why would we want to bother doing that?". He came up with the most astonishing

idea I'd ever heard, If I do this on the return from Wimp_Poll instead, so that your program

calls Wimp_Poll and instead of getting an answer back,

it get swapped out and someone else gets swapped in, and they get the return from the Wimp_Poll

that they called sometime earlier. Then we can actually have the full multi tasking system

that is RISC OS.

Going

back to Neil, he had a wizard idea, he said at the coffee machine one day "you know what,

if we fool around with MEMC we can do overlays, we can take an application program, use the

memory controller to whisk it away and map it somewhere else in the memory map and put another

program in at 0x8000 (which was where we mapped our applications too), the logical equivalent of PAGE on

the BBC Micro, we can do overlays, switch from one program to another. I thought "that's all very

well Neil but why would we want to bother doing that?". He came up with the most astonishing

idea I'd ever heard, If I do this on the return from Wimp_Poll instead, so that your program

calls Wimp_Poll and instead of getting an answer back,

it get swapped out and someone else gets swapped in, and they get the return from the Wimp_Poll

that they called sometime earlier. Then we can actually have the full multi tasking system

that is RISC OS.

Q: What did Wimp_Poll do before that? (In Arthur)

In the world of the Arthur 1.20 desktop, you called Wimp_Poll to the operating system, which is a SWI call and it would get any messages from the Mouse or Keyboard and return them too you, or quite often say 'null', there's nothing to do. So you'd sit there, polling away, responding to input. What Neil did was, you would call Wimp_Poll and that would see if there were any input messages for any other window, and if there was a message for another window, for another task, instead of returning the answer 'null' to you it would return to them, having poked around in MEMC to put their code into the space. They thought they'd made a call to Wimp_Poll and the very next thing as far as they were concerned was that they got their answer back, but actually you'd been running for a while in the mean time, because it had paged them out and put you in, you didn't even know they were there. I thought this was absolutely brilliant.

Q: So how did you run multiple clocks at once? (In the Arthur demo)

We just wrote a BASIC program that was allowed to draw itself lots of times, absolute fraud. If they'd said "Can you run two clocks and a calculator", I was screwed. But we went second and they went first, and they showed us their demo the night before and said "this is fabulous", and we wrote something that did exactly the same, but better. The thing was that their system was never going to fit on a machine that we were actually going to sell, so, all's fair, it needed doing.

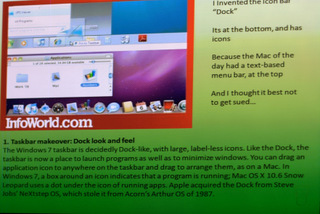

I'm coming

to the end of this now, I did a little bit of Googling for RISC OS, Arthur and

various other things and I found this page. I was very pleased by this, somebody

pointing out "the Windows 7 task bar is decidedly dock like with large label-less icons

like dock, this is now a place to launch programs as well as somewhere to minimise windows,

you can drag an application anywhere

on the taskbar and drag to arrange them, as on the Mac. In windows 7 the box around the icon

indicates that a program is running", blah blah blah, "Apple acquired the Dock from Steve Jobs'

NextStep OS which stole it from Acorn's Arthur Operating System of 1987". Damn right it did!

Tragically you couldn't patent software at that point. So this was the one I invented, I came

up with the idea of the iconbar across the bottom. In case anyone ever asked where it came

from, we were sat in a room thinking "how do we design this to be different, so we don't get

sued by Apple". The Mac of the day had a menu bar of text across the top, so we thought

"we can't go across the top, we'll have to go across the bottom and we can't use text so

we'll have to use icons", that's why it's like that.

I'm coming

to the end of this now, I did a little bit of Googling for RISC OS, Arthur and

various other things and I found this page. I was very pleased by this, somebody

pointing out "the Windows 7 task bar is decidedly dock like with large label-less icons

like dock, this is now a place to launch programs as well as somewhere to minimise windows,

you can drag an application anywhere

on the taskbar and drag to arrange them, as on the Mac. In windows 7 the box around the icon

indicates that a program is running", blah blah blah, "Apple acquired the Dock from Steve Jobs'

NextStep OS which stole it from Acorn's Arthur Operating System of 1987". Damn right it did!

Tragically you couldn't patent software at that point. So this was the one I invented, I came

up with the idea of the iconbar across the bottom. In case anyone ever asked where it came

from, we were sat in a room thinking "how do we design this to be different, so we don't get

sued by Apple". The Mac of the day had a menu bar of text across the top, so we thought

"we can't go across the top, we'll have to go across the bottom and we can't use text so

we'll have to use icons", that's why it's like that.

My proof that this is in fact true, have you ever asked yourself why some of the icons are on the right and some are on the left? Have you noticed that Windows has exactly the same distribution, some things go that side and some things go that side. We started off with having a world of physical devices on the left and application programs on the right. That was the rational for it in the first place, and it's exactly the same way, up to a point, in Windows. Printers and floppy drives, all turned up on this side. It's become a bit more confused in the later versions, generally when you ran things they appeared there and when you had things they appear there. So I think I'll come to the end of my rant and I'm happy to take any questions. or regale you with further amusing stories of some of the naughtiness that we got up to along the way that I didn't dare write down.

Q: ARX, who was actually developing it?

A group in Paolo Alto, there was a guy called Jim Mitchell that lead the ARX development team out there and a lot of very highly paid Californian software engineers writing it. It would have been absolutely wonderful, it just needed about another 20 years of Moore's Law to make it plausible.

Q: Was it started from scratch or based on something?

As a paradigm there was a Linux like core called Mach, a multi-threaded, multi-user core, they were trying to follow that, and built it up from that sort of base.

Q: A bit like Mac OS X?

Yeah a bit like Mac OS X, it wouldn't surprise me to find that some of those guys ended up working at Apple. There was a guy at Colton Software with us, Dave ???? who joined Microsoft in Seattle and it was shortly after that that Windows acquired an iconbar. I know how that idea got there.

Q: The board of directors at Acorn when you were there, were they technical people?

During the Arthur project, I think we had Brian Long as the CEO/Managing director, he was a financial man. Herman (Hauser) was technical director, in name, but Jim Merryman, the operations director was doing technical director role, because Herman and Chris (Curry) were too busy doing other things. No, none of them were particularly technical. The technical leads of the company were really Sophie (Wilson) and Steve Furber, and then people such as Tudor Brown and Mike Muller, who subsequent to that story separated off from the mothership and went off to be ARM.

Q: How important do you think it is that directors should have a background in electronics, hardware or programming?

I think if you look at the history of Acorn it was started by Chris (Curry) and Herman (Hauser), Herman was a deeply technical guy, I've a lot of respect for Herman. It was when those guys let go of control of the day to day side of it, shortly after this episode that things really started to go wrong. The rush to market, to release products before the right time, set in because the company had 300-400 employees and needed to feed them, and kept having to churn out new products, and the financial side of it was running it. Yes, it's vitally important that technical people with the vision to see where it's going are the ones that lead the company. You need the business people there to execute it, but if you let go of that technical vision, it goes pear-shaped.

Q: You say it all started to go wrong after the release of Arthur, when the technical guys let the finance guys take over, wasn't the whole story of Arthur basically a product being released before it was ready?

Yeah, the whole thing should have taken longer. I completely agree, I think the mad rush to design the hardware and get it out to market meant that it came out at a price point that was unaffordable, 700-1000 ukp was too much in the face of the competition, a 68000 based Amiga, at 500 ukp. We had a machine that was better, but more expensive, we didn't have an entry level product underneath.

So it was an extremely tough sell.

Q: I remember Sophie Wilson saying a similar thing when she gave a talk. In the experience of selling the Archimedes it was the high end models that got pulled first because people bought the low end ones, people cared more about price, than features.

Yeah, sadly exactly right, it was a wonderful machine.

Q: Did you have a role beyond Arthur?

No, I decided to leave, after about Arthur 1.60, I think I took it up to there, I left and was offered a lot of money to go and work for Clive Sinclair, building his machines. William Stoye took over from 1.60 through to 2.something when they renamed it RISC OS. 1.60 had all that Neil Raine magic in it, that happened on my watch. I went off to do other things and for about a year I designed, with Mark Colton, a machine for Clive Sinclair called the Z88 which was a laptop that ran on 4 AA batteries, the screen at the top and the black rubber keys, we had a lot of fun doing that. It had Pipedream in it that Mark had written and BBC BASIC which Richard Russell did, a nice machines. We were designing a follow on for it which was going to use an ARM processor and be in a nice magnesium case and then Clive, bless him, decided the future was satellite dishes, dropped doing computers and I went "you don't need any software for a satellite dish", so I set my own business up.

Q: Is that what happened to the 'Quantum Leap' ?

That had died sometime before, a long time before.

Q: You mentioned William Stoye. There was a Stoye who did some work on semantics in programming languages, now are they related, it's an unusual surname?

I think it might be the same person, that's what his PhD was in. He was in Acorn's R&D group when I decided to move on, and they got him too look after RISC OS.

Q: You mentioned you were in charge of the languages group, when it came to the Arthur Operating System, there didn't seem to be the same collection of languages available?

One of the things the history of it showed was that Acornsoft, a separate limited company, whose mission was to make money by selling software titles for Acorn's computers. We were in the same Group but a separate thing and when we got merged together and the Arthur project was born there was no Acornsoft to go and do the exploitation work. To build the software titles and the games, we had a game, that David Braben wrote 'Zarch', that was it. There was no Acornsoft games department ready to build all of those software titles. I remember after we got the operating system working, banging on about this for some time saying "look, this is all well and good, we've got this machine, but we need loads of application software for it like we had before in order to make it useful", but there was no resource to do that.

It took a fair time before various third parties, Computer Concepts and a whole bunch of others managed to catch up and start producing enough software. Impression, Rhapsody and all that that made it actually useful. It would have helped if we'd had the same group of guys beavering away churning out titles. There was still a belief within parts of Acorn that this was only a temporary solution and that the ARX stuff would come back, and there was another lot that was trying to build BSD UNIX that was going on as well. All the guys that they hired that were working on compilers were focusing on them, so it was absolutely ages before we had a compiler for anything. We couldn't get anyone to put any effort in to making the tools to go with the thing, because it was only an interim solution.

Q: Too quiet to hear

The A305 and A310 were the first machines, if we'd had a team of half a dozen people to write applications they could have started a year before that on the A500.

Q: Presumably that would have been your team if you hadn't had to take over from ARX?

Yes, it would have been us, but we were writing the operating system, it would have been our job to build all that stuff for people.

Q: Sometime afterwards there was a PC emulator?

Yes, a guy called Ian Jack wrote the PC emulator, he wasn't part of my team, but he was in the next door office. A 186 emulator, and then a 286.

Q: Are you surprised that RISC OS still attracts so many of us?

Yes, I think you're all bonkers.

Q: Is it nostalgia?

I think it is, but we did a good job given the mad history of it all and I wish my computer would boot in 2 seconds. It does my head in every day when I confront Microsoft Windows and think what things could have been like. Over time, Windows particularly, and some of the Mac stuff has evolved more and more to look like RISC OS. You've all got iPads and things like that, does that all feel horribly familiar?

Q: The Arthur way you can only run one application at a time?

Yeah exactly!

I think it is fantastic that things like the Raspberry Pi are coming out. David Braben has done a lot to publicise that, not because he thinks RISC OS is wonderful, but that we really want to encourage a whole new generation of people to understand the technology. I've got my software businesses but I can't hire anyone who knows what is going on. It's very rare these days that someone knows what an interrupt is, knows how to poke a register or how to debug anything when the tools don't work. It's quite a problem.

I won't tell you the story about who was arrested on the premises!

Not only did we not have not have any tools or compilers. All we had was an assembler.

Q: The BASIC assembler?

No John Thackery had done an assembler for the ARM development kit, we used that. That and the BASIC interpreter, that was it.

We had no source control, we had 7 or 8 guys trying to write an operating system to go into a ROM, so you've got to get it right, and they're all doing different bits of it and some of these share system files. No CVS, no source control, no Sourcesafe, none of that. The solution was the main system header file with all the constants, SWI numbers and addresses of everything lived in. You could edit that if you had the pink dinosaur on your desk. If you did not have the pink dinosaur on your desk you could not edit it. If you edited it without the pink dinosaur, my Australian friend, Brian Cockburn, would come round and see you. I remember a squealing as Stuart had made some interesting macro changes to the header system without the dinosaur and Brian had spent most of the night trying to figure out why his stuff didn't work, and had finally found out and had got Stuart cowering under the desk saying "come on I want to do the other arm", after giving him a chinese-burn on one arm.

I remember going to one of the first shows down at Olympia when we were launching stuff. Acorn had a massive stand there and we had one Archimedes A310 on one end, and on the other end lots of the Acorn marketing guys in suits with the Acorn ABC, the awful things that Olivetti had forced them to do. Myself and Stuart there, I had my very ancient brown jumper on and Stuart with orange hair 'out here'. There was a great mob around us to see what we were showing with Arthur 1.20 and you could hear the suited Acorn sales guys saying "no, no, no, I don't know anything about it, you need to either speak to him with the jumper or him with the hair".

* Actually shadow RAM was invented by Chris Jordan and David Barnett, and first marketed by Aries Computers